Conditional Immortality (Annihilationism) vs. Conscious Eternal Punishment

Does an Unbeliever Experience Destruction or Eternal Torture?

Kirk Cameron lit up the Christian blogs, podcasts, and platforms recently with controversial statements regarding the nature of hell and eternal punishment. As I listened to his setup of how he started to wrestle with this question, it challenged me to dig into scripture and historical positions of church leaders in order to understand the two postioins.

So, off I went to Claude to help me dig deep! This document was created with three separate prompts.

Give me the biblical support and argument for Conditional Immortality

Give me the biblical support and argument for Eternal Conscious Punishment

Which one of these positions offers more biblical support

This question has become more prevalent and important in the recent days of theological study and conjecture. Here is a set of arguments for both positions and a conclusion of which has more Biblical support. Please read through the entire document. This is not a position paper for either argument, but a presesntation of both arguments with a conclusion of strengths and weaknesses of both.

The Biblical Case for Conditional Immortality (Annihilationism)

This is a thoughtful question that touches on one of the more significant intra-evangelical debates of the past century. Conditional immortality—often termed “annihilationism”—has been advocated by serious evangelical scholars such as John Stott, Edward Fudge, Clark Pinnock, and more recently Preston Sprinkle, all of whom affirm the full authority and inspiration of Scripture.

Let me walk you through the biblical case as its proponents articulate it, examining the relevant texts and the Hebrew and Greek terminology at play.

The Semantic Foundation: Biblical Language of Final Judgment

The Greek Term Apollymi (ἀπόλλυμι)

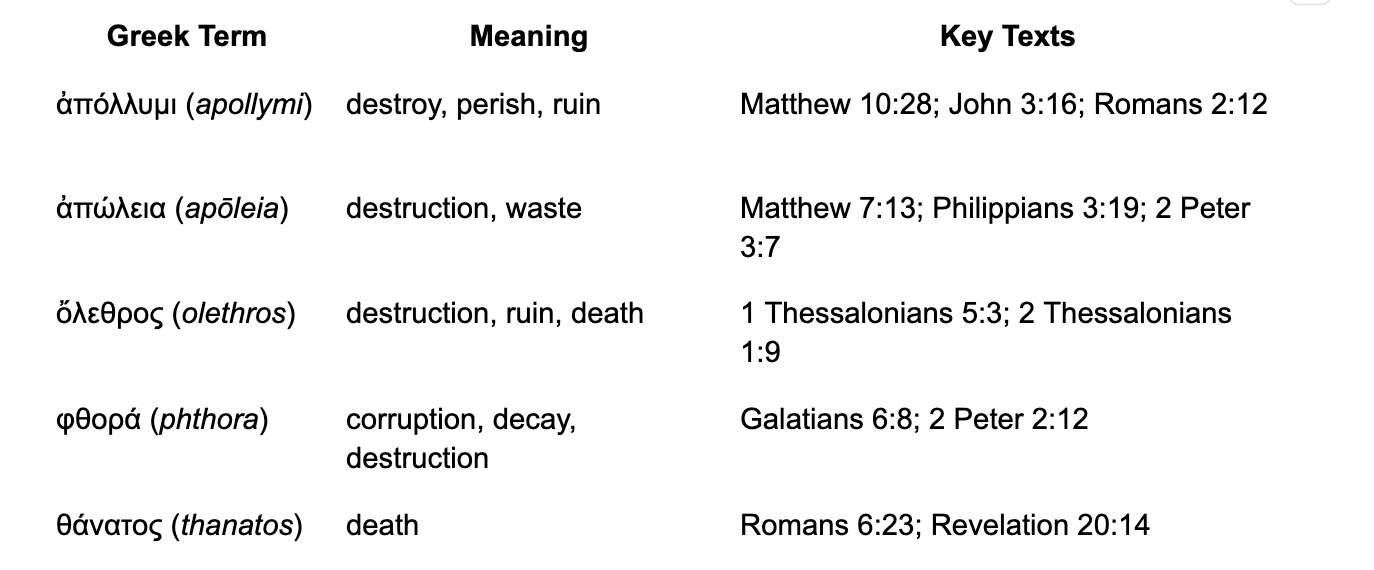

One of the most frequently used words in the New Testament regarding the fate of the wicked is ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi), which carries the fundamental meaning “to destroy utterly, to perish, to be ruined.” Conditionalists argue that this word, used over 90 times in the New Testament, consistently denotes actual destruction rather than preservation in torment.

Consider Jesus’ words in Matthew 10:28 (NASB):

“Do not fear those who kill the body but are unable to kill the soul; but rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.”

The verb here is ἀπολέσαι (the aorist infinitive of apollymi). Conditionalists argue that Jesus distinguishes between what humans can do (kill the body) and what God alone can do (destroy both soul and body). The parallel structure suggests genuine destruction of the whole person, not eternal preservation in suffering.

The Contrast of John 3:16

Perhaps the most beloved verse in Scripture presents a stark binary:

“For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish (ἀπόληται), but have eternal life.”

The contrast is between perishing and eternal life—not between two forms of eternal existence. Conditionalists suggest that taking apollymi at face value here yields a straightforward reading: those who reject Christ will cease to exist, while those who believe receive the gift of immortality.

Romans 6:23 and the Wages of Sin

Paul’s famous declaration reinforces this framework:

“For the wages of sin is death (θάνατος, thanatos), but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Again, the antithesis is between death and life—not between two modes of eternal conscious existence. Conditionalists argue that the natural reading of thanatos throughout Scripture denotes the cessation of life, not its continuation in another form.

Old Testament Imagery: Fire That Consumes

The Hebrew prophets employ vivid imagery that conditionalists find instructive. The language consistently describes the wicked as being consumed rather than preserved.

Malachi 4:1-3 (NASB)

“For behold, the day is coming, burning like a furnace; and all the arrogant and every evildoer will be chaff; and the day that is coming will set them ablaze,” says the LORD of hosts, “so that it will leave them neither root nor branch... You will tread down the wicked, for they will be ashes under the soles of your feet.”

The Hebrew אֵפֶר (epher)—ashes—suggests complete consumption. Chaff does not burn eternally; it is consumed and ceases to exist. This aligns with John the Baptist’s later warning that the Messiah would “burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire” (Matthew 3:12). The fire is unquenchable not because the chaff burns forever, but because nothing can extinguish it until its consuming work is complete.

Psalm 37:20

“But the wicked will perish; and the enemies of the LORD will be like the glory of the pastures, they vanish—like smoke they vanish away.”

The Hebrew verb כָּלָה (kalah) means “to be complete, finished, consumed.” The simile of vanishing smoke powerfully communicates dissolution rather than perpetuity.

The “Eternal” Question: Aionios (αἰώνιος)

Traditional interpreters often point to Matthew 25:46 as decisive:

“These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

The Greek αἰώνιος (aionios) modifies both “punishment” and “life.” The traditional argument holds that if “life” is everlasting in duration, so must be the “punishment.”

Conditionalists offer two responses:

The nature versus duration distinction: Aionios may describe the quality or source (pertaining to the age to come, originating from God) rather than strictly infinite duration. The punishment is “eternal” in that it is final and irreversible—not that the process of punishing continues forever.

Punishment versus punishing: The noun κόλασις (kolasis) refers to the result of punishment, not necessarily an ongoing process. Compare “eternal redemption” (Hebrews 9:12)—Christ does not continue redeeming forever; rather, the result of His redemptive act is eternal. Similarly, “eternal punishment” may refer to a punishment whose consequences are everlasting (i.e., permanent destruction).

2 Thessalonians 1:9—Destruction from the Presence

Paul writes concerning those who do not obey the gospel:

“These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction (ὄλεθρον αἰώνιον), away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power.”

The Greek ὄλεθρος (olethros) fundamentally means “ruin, destruction, death.” Conditionalists argue that “eternal destruction” most naturally means a destruction that is permanent and final—not an eternal process of being destroyed.

This aligns with how the Septuagint (the Greek Old Testament) uses similar terminology for the fate of the wicked in passages like Psalm 92:7.

The Second Death: Revelation 20:14-15

John’s apocalyptic vision describes the final judgment:

“Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire. And if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire.”

Conditionalists observe that this is called θάνατος δεύτερος—the “second death”—not “second life” or “eternal torment.” Death is the cessation of life. The imagery suggests finality: even death itself is destroyed.

Jude 7 and Sodom as Paradigm

Jude provides interpretive guidance:

“Just as Sodom and Gomorrah and the cities around them... are exhibited as an example in undergoing the punishment of eternal fire.”

The cities of the plain are not still burning today. Yet their destruction by fire is called “eternal” because the results are permanent. The fire accomplished its consuming work and ceased. Conditionalists suggest this provides a hermeneutical key for understanding “eternal fire” elsewhere.

Immortality as Gift, Not Inherent Possession

A crucial theological point undergirds the conditionalist position: immortality belongs to God alone and is granted to believers as a gift.

Paul declares in 1 Timothy 6:16 that God “alone possesses immortality.” And in 1 Corinthians 15:53-54, immortality is something believers “put on” at the resurrection:

“For this perishable must put on the imperishable, and this mortal must put on immortality.”

Conditionalists argue that the traditional view assumes the inherent immortality of the soul—a concept more at home in Platonic philosophy than in Hebrew anthropology. Michael Heiser, whom you appreciate, would note that the Hebrew understanding of נֶפֶשׁ (nephesh) describes the whole living person, not an immortal soul temporarily housed in a body. If immortality is a gift given only to those in Christ, then those outside Christ may simply cease to exist.

Historical Witnesses

While the traditional view of eternal conscious torment became dominant through Augustine’s influence, conditionalist ideas appear in earlier Christian writings:

Ignatius of Antioch (c. 110 AD) wrote that heretics “shall go into the unquenchable fire” and elsewhere spoke of non-believers “dying.”

Irenaeus (c. 180 AD) taught that the soul is not inherently immortal and that eternal life is granted through Christ.

Arnobius of Sicca (c. 300 AD) explicitly taught that the wicked would be consumed and cease to exist.

Even Justin Martyr, one of your noted historical references, wrote in his Dialogue with Trypho that souls are not inherently immortal but die unless God wills them to live.

Where Scripture Affirms Scripture

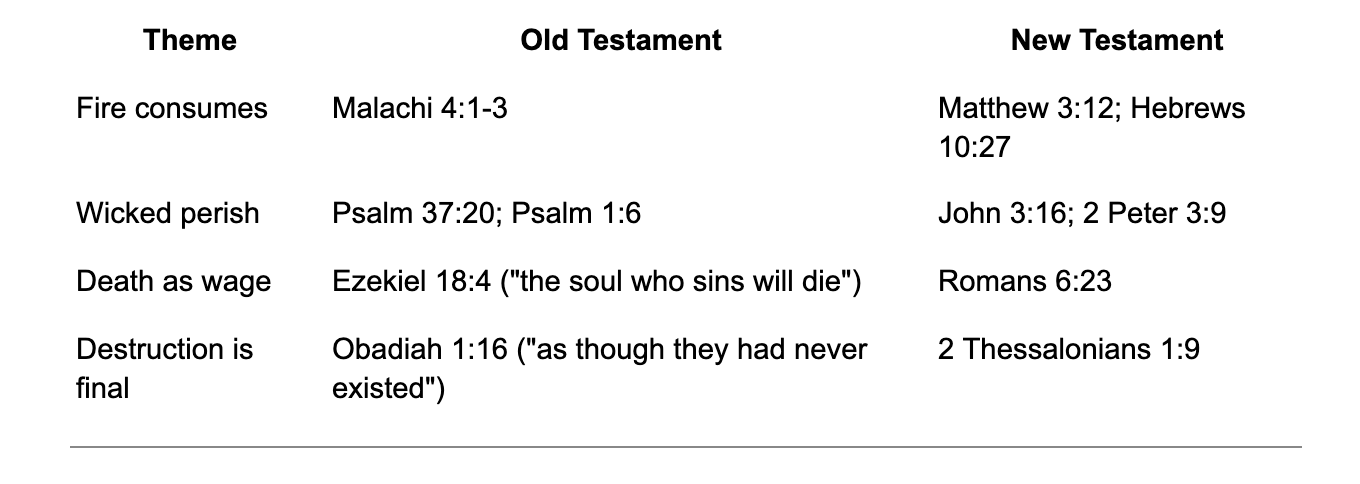

The conditionalist case gains strength from its internal coherence across the biblical corpus:

A Pastoral and Intellectual Consideration

What draws many sincere believers to this position is not a desire to “soften” the doctrine of hell, but rather a conviction that it allows the biblical text to speak on its own terms. As Edward Fudge argued in The Fire That Consumes, the traditional view requires us to interpret “destroy,” “perish,” “death,” and “consume” as meaning something quite different from their ordinary usage.

Watchman Nee, one of your favored teachers, emphasized the importance of allowing Scripture to interpret Scripture rather than imposing philosophical frameworks upon the text. Conditionalists believe their reading honors that hermeneutical commitment.

A Word of Humility

This remains a contested issue among those who equally affirm biblical authority. Scholars like D.A. Carson, Robert Peterson, and many others have offered substantive defenses of the traditional view. The question is not whether final judgment is real—Scripture is unequivocal on that point—but what form that judgment takes.

What is certain is that Jesus spoke with utmost seriousness about the fate of the impenitent, and we should approach this topic with the gravity it deserves. As Jesus Himself urged in Matthew 10:28, we are to fear the One who holds such power over our eternal destiny—and run to Him as the only source of life.

The Biblical Case Against Conditional Immortality: The Traditional View of Eternal Conscious Punishment

Having examined the conditionalist position, intellectual honesty requires we give equal weight to the traditional view, which has been the dominant understanding throughout church history. Scholars such as D.A. Carson, Robert Peterson, Christopher Morgan, and J.I. Packer have articulated robust biblical defenses of eternal conscious punishment. Let me present their case with the same rigor.

The Weight of Church History

Before examining the texts, we should acknowledge that the traditional view has been the overwhelming consensus of the church for nearly two millennia. While historical consensus does not settle theological questions, it does warrant epistemic humility before departing from it.

Augustine articulated the position definitively in City of God, but he was not its originator. Tertullian (c. 200 AD), Cyprian (c. 250 AD), and John Chrysostom (c. 400 AD) all taught eternal conscious punishment. Josephus, your noted historical source, records that the Pharisees of Jesus’ day believed in eternal punishment for the wicked—the very theological context in which Jesus taught.

As Eusebius documents in his Ecclesiastical History, the earliest post-apostolic writers understood Christ’s warnings about hell to describe ongoing conscious suffering. If the conditionalist view were the apostolic teaching, we would expect clearer evidence of it in the earliest centuries.

The Decisive Text: Matthew 25:41-46

Jesus’ teaching on the final judgment stands as the cornerstone of the traditional position:

“Then He will also say to those on His left, ‘Depart from Me, accursed ones, into the eternal fire which has been prepared for the devil and his angels... These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” (NASB)

The Parallel Structure Argument

The Greek adjective αἰώνιος (aionios) modifies both κόλασιν (kolasin, “punishment”) and ζωήν (zōēn, “life”). The grammatical parallelism is exact:

κόλασιν αἰώνιον — eternal punishment

ζωὴν αἰώνιον — eternal life

Traditional interpreters argue that linguistic integrity demands consistency. If aionios means “everlasting in duration” when applied to the life of the righteous, it must mean the same when applied to the punishment of the wicked. To assign different meanings to the same adjective in the same sentence, in parallel construction, violates basic hermeneutical principles.

As Matthew Henry observes in his commentary, “The sentence is not parallel if one is temporary and the other eternal; Christ puts them together to show they share the same quality of endlessness.”

The Nature of Kolasis

Conditionalists argue that κόλασις refers to the result of punishment rather than an ongoing process. However, the word fundamentally denotes the experience of punishment—the conscious suffering of the one being punished. In classical Greek usage (Aristotle, Plato) and in the Septuagint, kolasis consistently refers to corrective or retributive suffering experienced by the recipient.

If Jesus meant to communicate annihilation, Greek offered Him clearer options: θάνατος (thanatos, death), ἀπώλεια (apōleia, destruction), or ἀφανισμός (aphanismos, disappearance). Instead, He chose a word that inherently implies conscious experience.

The Rich Man and Lazarus: Luke 16:19-31

While some dismiss this passage as “merely a parable,” Jesus’ account of the rich man in Hades provides significant data:

“In Hades he lifted up his eyes, being in torment, and saw Abraham far away and Lazarus in his bosom. And he cried out and said, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus so that he may dip the tip of his finger in water and cool off my tongue, for I am in agony in this flame.’... And besides all this, between us and you there is a great chasm fixed, so that those who wish to come over from here to you will not be able, and that none may cross over from there to us.”

Key Observations

Conscious experience: The rich man sees, speaks, feels thirst, experiences agony. This is not the language of non-existence.

The Greek terminology: The word for “torment” is βασάνοις (basanois), denoting torture or severe pain consciously experienced. The word for “agony” is ὀδυνῶμαι (odynōmai), meaning “I suffer pain.”

The fixed chasm: The permanence suggested by the “great chasm fixed” (χάσμα μέγα ἐστήρικται) implies an unchangeable state, not a temporary condition preceding annihilation.

Present-tense suffering: Even if this describes the intermediate state (Hades) rather than the final state (Gehenna), it demonstrates that conscious suffering of the wicked is a biblical category. If the intermediate state involves conscious torment, why would the final state involve less?

Traditional interpreters note that even if this is a parable, Jesus would not teach falsehood through His illustrations. The theological content must be reliable, or the entire teaching collapses.

Revelation: The Testimony of the Apocalypse

The Book of Revelation provides the most explicit language regarding the duration of punishment.

Revelation 14:9-11

“If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives a mark on his forehead or on his hand, he also will drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is mixed in full strength in the cup of His anger; and he will be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever; they have no rest day and night, those who worship the beast and his image.”

The traditional case here is formidable:

“Forever and ever”: The Greek phrase εἰς αἰῶνας αἰώνων (eis aiōnas aiōnōn) is the strongest expression of unending duration available in Greek. This exact phrase is used of God’s own eternal existence (Revelation 4:9-10, 10:6, 15:7) and of the reign of the saints (Revelation 22:5). If it means “unending” when applied to God and to the saints’ reign, consistency demands it mean the same here.

“No rest day and night”: The phrase οὐκ ἔχουσιν ἀνάπαυσιν ἡμέρας καὶ νυκτός describes ongoing, unceasing experience. Annihilation would be the ultimate “rest”—cessation of consciousness. But John explicitly denies rest to those under judgment.

“Tormented” (βασανισθήσεται): Again, the language of conscious suffering, not extinction.

Revelation 20:10

“And the devil who deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are also; and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.”

The devil, beast, and false prophet experience conscious torment “forever and ever” (eis tous aiōnas tōn aiōnōn). Verse 15 then states that anyone not found in the book of life is thrown into “the same lake of fire.” The natural reading is that they share the same fate—eternal conscious torment—not a different fate of annihilation.

The Conditionalist Response and Its Weakness

Conditionalists often argue that the “smoke” ascending forever is imagery of completed destruction (like Sodom’s smoke in Genesis 19:28). But the text does not say merely that smoke rises; it says “the smoke of their torment”—genitive of source. The smoke derives from ongoing torment, not from completed combustion. And the phrase “no rest day and night” cannot describe beings who no longer exist.

Mark 9:42-48: The Worm That Does Not Die

Jesus’ warnings in Mark 9 draw on Isaiah 66:24 and present powerful imagery:

“If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life crippled, than, having your two hands, to go into hell, into the unquenchable fire, where their worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched.”

The Greek and Hebrew Background

The Greek σκώληξ (skōlēx, “worm”) corresponds to the Hebrew תּוֹלָע (tola) in Isaiah 66:24. Jesus quotes Isaiah: “Their worm will not die and their fire will not be quenched.”

Traditional interpreters argue:

The worm “does not die” (οὐ τελευτᾷ): If the objects of judgment were annihilated, the worms consuming them would cease their work. But Jesus emphasizes their persistence.

The fire “is not quenched” (οὐ σβέννυται): Conditionalists argue that “unquenchable” means the fire cannot be extinguished until it finishes its work. But the point of Jesus’ language is the endlessness of the process, not merely its unstoppability during a finite period.

The imagery of ongoing consumption: Worms consume dead bodies; fire consumes material. If both worm and fire persist without end, so must the objects they act upon.

As A.W. Tozer wrote, “The notion that God’s wrath will simply cause cessation of being removes the moral gravity from Christ’s most urgent warnings.”

The Argument from Divine Justice

Proportionality and Infinite Offense

Traditional theology argues that sins against an infinitely holy God constitute infinite offenses, warranting infinite punishment. Anselm of Canterbury articulated this in Cur Deus Homo: the gravity of an offense is measured not merely by the act itself but by the dignity of the one offended.

Jonathan Edwards developed this further: “The crime of one being despising and casting contempt on another is proportionably more or less heinous, as he was under greater or less obligations to obey him. And therefore if there be any being that we are under infinite obligations to love, honour and obey, then to sin against him is a crime infinitely heinous.”

If sin against the infinite God constitutes an infinite evil, finite punishment—including the finality of annihilation—would represent an insufficient response to that evil.

The Problem of Retrospective Justice

Conditionalism effectively holds that Adolf Hitler and a relatively moral unbeliever will eventually share the same fate: non-existence. Once annihilated, there is no ongoing difference in their condition. But Scripture suggests degrees of punishment (Luke 12:47-48, Matthew 11:22-24), which implies ongoing conscious states that can admit of gradation. Non-existence has no degrees.

The Argument from Redemption’s Value

If the alternative to salvation is merely non-existence, the costliness of redemption is diminished. Consider the logic:

Christ endured the Father’s wrath on the cross to rescue sinners.

If sinners faced only cessation of existence, Christ would have needed only to cease existing temporarily.

But Christ’s suffering involved conscious agony, spiritual abandonment, and the experience of divine judgment.

The traditional view maintains that Christ’s sufferings correspond to what sinners themselves would otherwise experience. His cry, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” reflects conscious experience of divine wrath—not mere termination of existence.

Oswald Chambers, whom you appreciate, wrote: “The Cross is the exhibition of the nature of God—and the Cross revealed what sin deserves. Not termination, but the full weight of holy judgment.”

Addressing Conditionalist Proof Texts

On “Destruction” Language

Conditionalists emphasize words like ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi, “destroy, perish”). But this word carries a semantic range broader than physical annihilation. Consider:

Matthew 9:17: Wineskins are “ruined” (apollyntai)—not annihilated but rendered useless.

Luke 15:4, 6, 24: The lost sheep, lost coin, and prodigal son were “lost” (apōlōs)—not non-existent, but separated from their proper place and purpose.

John 6:12: Leftover bread fragments might “perish” (apolētai)—go to waste, not vanish from existence.

The word fundamentally means “ruined, lost, destroyed in terms of purpose”—not necessarily “reduced to non-being.” The wicked are “destroyed” in that they are ruined, separated from God’s blessing, and have forfeited their intended purpose.

On “Death” as the Wages of Sin

Yes, “the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23). But biblical “death” consistently refers to separation, not annihilation:

Physical death: Separation of soul from body

Spiritual death: Separation of person from God (Ephesians 2:1—”dead in trespasses and sins,” yet clearly still existing and conscious)

Eternal death: Permanent separation from God’s gracious presence

When Ephesians 2:1 describes unbelievers as “dead,” they obviously still exist. The “second death” of Revelation may similarly describe an intensified state of separation rather than extinction.

On Immortality as a Gift

Conditionalists argue that immortality is granted only to believers (1 Timothy 6:16). But the text says God alone possesses immortality intrinsically—not that He cannot grant ongoing existence to others. Even in conditionalist theology, God sustains the wicked long enough to judge them. The question is whether He continues to sustain their existence thereafter, and the texts examined above suggest He does.

Historical-Theological Consistency

The Hebrew View of Sheol

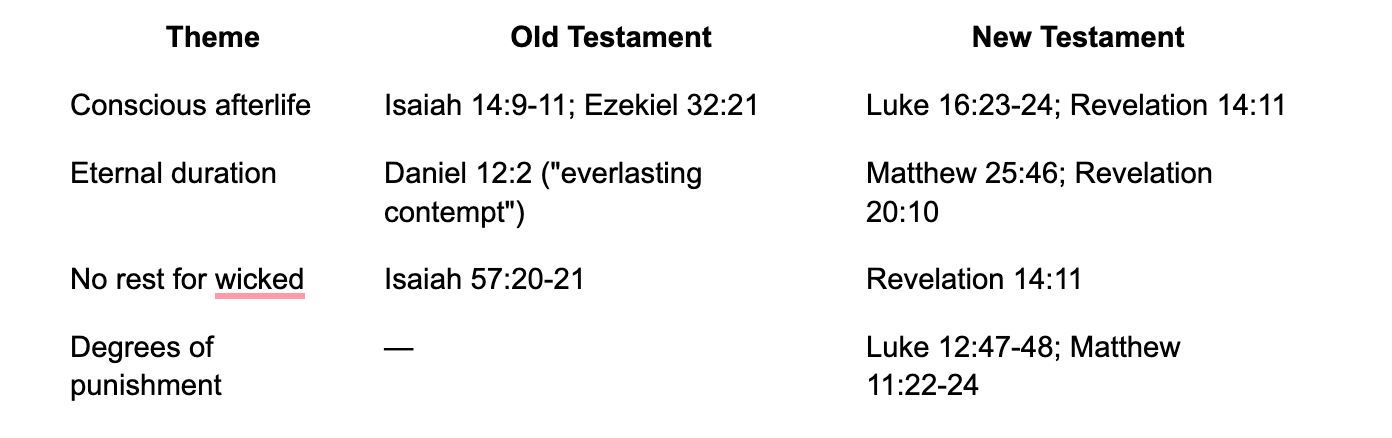

The Old Testament concept of שְׁאוֹל (Sheol) portrays the dead as existing in a shadowy realm, not as annihilated. The dead in Sheol are described as conscious though diminished (Isaiah 14:9-11, Ezekiel 32:21). This provides the conceptual backdrop for New Testament teaching on the intermediate and final states.

Second Temple Judaism

Josephus records that the Pharisees (whose theology Jesus largely affirmed) believed in eternal punishment for the wicked. The Book of Enoch, though not canonical, reflects widespread Jewish belief in ongoing conscious punishment. Jesus’ Jewish audiences would have understood His warnings in this context.

The Apostolic Fathers

2 Clement (c. 100-150 AD) warns: “If we do the will of Christ, we shall find rest; but if not, nothing shall deliver us from eternal punishment.”

Ignatius of Antioch (c. 110 AD): “Those who corrupt families by adultery shall not inherit the kingdom of God. And if they that do these things according to the flesh have suffered death, how much more shall he die who corrupts by evil doctrine the faith of God for which Jesus Christ was crucified! Such a one becoming defiled shall depart into unquenchable fire.”

The consistent early witness supports the traditional reading.

Where Scripture Affirms Scripture: The Traditional Framework

Daniel 12:2 is particularly significant:

“Many of those who sleep in the dust of the ground will awake, these to everlasting life, but the others to disgrace and everlasting contempt.”

The Hebrew דְּרָאוֹן (dera’on, “contempt, abhorrence”) implies something that continues to be viewed with revulsion—which requires the ongoing existence of the object of that contempt.

A Pastoral Word

Both positions are held by those who deeply reverence Scripture’s authority. The traditional view, however, maintains that the weight of exegetical evidence, the grammatical structures of key texts, the church’s historical consensus, and the internal logic of redemption favor eternal conscious punishment.

Ray Vanderlaan, whom you appreciate, often emphasizes reading Scripture within its cultural and theological context. The Second Temple Jewish context in which Jesus taught assumed conscious afterlife and eternal consequences. Jesus intensified these warnings rather than correcting them.

The doctrine is sobering beyond words—and it is meant to be. Jesus spoke more about hell than anyone else in Scripture. His warnings were not philosophical abstractions but urgent pleas to flee the coming wrath. The traditional view takes those warnings with utmost seriousness.

As Augustine wrote in City of God: “So then what God by His prophet has said of the everlasting punishment of the damned shall come to pass—shall without fail come to pass.”

An Honest Assessment: Weighing the Biblical Evidence

This is precisely the question a serious student of Scripture should ask. Let me offer a candid evaluation, examining where each position demonstrates exegetical strength and where each faces its most significant challenges.

The Hermeneutical Reality

Both positions marshal substantial biblical support. The question is not which view has any justification, but which view better accounts for the totality of the relevant texts while requiring fewer strained interpretations.

I’ll be direct: the traditional view possesses certain texts that are exceptionally difficult for conditionalists to address, while the conditionalist view better accounts for the broader semantic patterns of Scripture’s destruction language.

Let me explain.

Where the Traditional View Holds Stronger Ground

The Revelation 14:9-11 Problem

This text presents the most formidable challenge to conditionalism:

“The smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever; they have no rest day and night.”

The phrase οὐκ ἔχουσιν ἀνάπαυσιν ἡμέρας καὶ νυκτός (”they have no rest day and night”) is exceedingly difficult to reconcile with annihilation. Consider:

Annihilation would be the ultimate rest—complete cessation of consciousness

The text explicitly denies rest to those under judgment

The present tense ἔχουσιν (”they have”) suggests ongoing state, not completed action

Conditionalist responses to this text tend to be the least persuasive part of their case. Edward Fudge argues the imagery is symbolic of completed judgment, pointing to Isaiah 34:10 where Edom’s smoke “rises forever” though Edom is not literally still burning. However, Isaiah 34 lacks the crucial phrase “no rest day and night.” That addition in Revelation 14 significantly changes the interpretive picture.

Verdict: The traditional view handles this text more naturally.

The Matthew 25:46 Parallel

“These will go away into eternal punishment (κόλασιν αἰώνιον), but the righteous into eternal life (ζωὴν αἰώνιον).”

The grammatical parallelism here is genuinely significant. The same adjective modifies both nouns in identical syntactical construction. While conditionalists argue that aionios can describe the quality or finality of punishment rather than its duration, this requires assigning different semantic values to the same word in the same sentence.

This is not impossible—words do carry different nuances in different contexts—but it places a heavier interpretive burden on the conditionalist reading.

Verdict: The traditional view has the more straightforward reading, though the conditionalist interpretation is not exegetically impossible.

Revelation 20:10 and the Lake of Fire

“And the devil who deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are also; and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.”

The explicit statement that the devil, beast, and false prophet are “tormented day and night forever and ever” (βασανισθήσονται ἡμέρας καὶ νυκτὸς εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων) uses the strongest durational language available in Greek—the same phrase used of God’s own eternal existence.

Verse 15 then states that those not in the book of life are thrown into “the same lake of fire.” The natural inference is that they share the same fate.

Conditionalists respond that the beast and false prophet may be symbolic entities (not individual beings) and that humans might experience a different fate. This is possible but requires reading a distinction into the text that is not explicitly present.

Verdict: The traditional view has the more natural reading.

Mark 9:48—The Undying Worm

“Where their worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched.”

The emphasis on the worm not dying (ὁ σκώληξ αὐτῶν οὐ τελευτᾷ) and the fire not being quenched suggests ongoing process rather than completed consumption. If the objects of judgment were annihilated, one would expect the consuming agents (worm, fire) to cease their activity.

Conditionalists argue that “unquenchable” simply means the fire cannot be resisted or extinguished prematurely—it will accomplish its consuming work. This is lexically possible (the Hebrew כָּבָה in Isaiah 66:24 can mean “extinguish” in the sense of “put out before completion”). However, the pairing with “the worm does not die” tilts the imagery toward perpetuity.

Verdict: The traditional view has a slight advantage, though the conditionalist reading is defensible.

Where the Conditionalist View Holds Stronger Ground

The Semantic Field of Destruction

The conditionalist case gains considerable strength from the cumulative weight of Scripture’s destruction vocabulary. Consider the breadth of terms:

Across dozens of passages, the fate of the wicked is described using terminology whose natural semantic range denotes cessation, ruin, and destruction—not preservation in torment.

The traditional view must consistently argue that these words mean something other than their ordinary sense. While possible for individual texts, the cumulative pattern is striking.

Verdict: The conditionalist view better honors the face-value meaning of Scripture’s dominant vocabulary for final judgment.

The Life/Death Antithesis

Scripture repeatedly frames the human choice as between life and death, not between two forms of eternal existence:

“I have set before you life and death... choose life” (Deuteronomy 30:19)

“The wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life” (Romans 6:23)

“Whoever believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16)

“The one who sows to his own flesh will from the flesh reap corruption, but the one who sows to the Spirit will from the Spirit reap eternal life” (Galatians 6:8)

The consistent biblical antithesis is life versus death, existence versus perishing, immortality versus corruption. The traditional view must redefine “death” as “eternal conscious existence in separation from God”—a meaning that requires significant theological inference rather than natural reading.

Verdict: The conditionalist framework better aligns with Scripture’s overarching life/death contrast.

The Old Testament Background

The Hebrew Scriptures consistently portray the fate of the wicked as destruction and consumption:

Psalm 37:20: “But the wicked will perish... like smoke they vanish away”

Psalm 1:6: “The way of the wicked will perish”

Malachi 4:1-3: “All the arrogant and every evildoer will be chaff... they will be ashes under the soles of your feet”

Obadiah 1:16: “They will be as if they had never existed”

The imagery is remarkably consistent: chaff burned up, smoke vanishing, ashes remaining, existence ceasing. Jesus and the apostles were saturated in this scriptural vocabulary. When they spoke of the wicked being “destroyed,” their Jewish audiences would naturally hear this against the Old Testament background of actual destruction.

Verdict: The conditionalist view maintains stronger continuity with Old Testament imagery.

The Immortality Question

The conditionalist argument regarding the source of immortality carries significant theological weight:

1 Timothy 6:16: God “alone possesses immortality”

1 Corinthians 15:53-54: Believers “put on” immortality at the resurrection

2 Timothy 1:10: Christ “brought life and immortality to light through the gospel”

If immortality is a gift granted through union with Christ, then the assumption that the wicked possess inherent immortality requires justification. The traditional view often assumes (consciously or not) the Platonic concept of the soul’s natural immortality—a philosophical framework foreign to Hebrew anthropology.

Michael Heiser, whom you appreciate, consistently emphasized reading Scripture through its ancient Near Eastern context rather than through Greek philosophical categories. The Hebrew concept of נֶפֶשׁ (nephesh) describes the whole living person, not an immortal soul temporarily inhabiting a body.

Verdict: The conditionalist view rests on a more biblically grounded anthropology.

The Critical Evaluation

Where Conditionalism Struggles

The conditionalist position faces its greatest challenge in the specific, explicit statements of Revelation 14:9-11 and 20:10. The language of “no rest day and night” and “tormented forever and ever” requires conditionalists to:

Interpret “forever and ever” differently than when applied to God’s existence or the saints’ reign

Explain how those who no longer exist can have “no rest”

Distinguish the fate of humans from that of the devil, beast, and false prophet in the same lake of fire

These are not insurmountable challenges, but the explanations required are less natural than the traditional reading of these specific texts.

Where the Traditional View Struggles

The traditional position faces its greatest challenge in the pervasive, repeated vocabulary of destruction across the canon. Traditionalists must:

Consistently interpret “destroy,” “perish,” “death,” and “consume” as meaning something other than their ordinary sense

Explain why Scripture frames the choice as “life versus death” rather than “blessed existence versus tormented existence”

Account for the Old Testament imagery of the wicked being consumed like chaff and vanishing like smoke

Justify the assumption of inherent human immortality from Scripture rather than philosophy

My Assessment (Claude AI Engine)

If I were forced to render a verdict on which view offers more biblical justification, I would frame it this way:

The traditional view has the stronger specific texts—particularly Revelation 14:9-11 and 20:10—which are difficult to reconcile with annihilation without significant interpretive moves.

The conditionalist view has the stronger cumulative case—the overwhelming preponderance of destruction language, the life/death antithesis, the Old Testament background, and the biblical anthropology of immortality as gift.

This creates a genuine hermeneutical tension:

Do we allow a few explicit statements (primarily in apocalyptic literature) to control the meaning of dozens of passages using destruction vocabulary?

Or do we allow the broader semantic patterns to shape how we interpret the more symbolic language of Revelation?

Sincere, Scripture-honoring scholars have landed on both sides of this question.

A Third Consideration: Interpretive Humility

Watchman Nee often emphasized that some truths in Scripture exist in tension, and our systematic theologies must hold space for mystery. A.W. Tozer warned against “the curse of the tidy systematizer” who forces every text into a predetermined framework.

What is absolutely certain from Scripture:

Final judgment is real and terrifying

The fate of the impenitent is described as worse than any temporal suffering

Jesus spoke with utmost urgency about fleeing the coming wrath

The separation from God is permanent and irreversible

The gospel offers rescue from this fate through Christ alone

What remains debated among those who affirm biblical authority:

The precise nature of that final state

Whether consciousness continues eternally or ceases after judgment

A Pastoral Conclusion

Perhaps Ray Vanderlaan’s approach is instructive here. He consistently emphasizes that the Hebrew mindset was less concerned with systematic precision than with faithful response. The biblical authors were not writing systematic theology textbooks; they were issuing urgent warnings and glorious invitations.

Whether the final fate of the impenitent is eternal conscious torment or permanent destruction after judgment, the call of Scripture remains the same: “Flee from the wrath to come” (Matthew 3:7) and “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved” (Acts 16:31).

Either view does not diminish the severity of the warning. Both positions affirm that rejection of Christ leads to a fate of unspeakable loss—either endless suffering or the irrevocable forfeiture of existence itself. Neither position offers comfort to the impenitent.